Vertigo Treated with Home Exercises

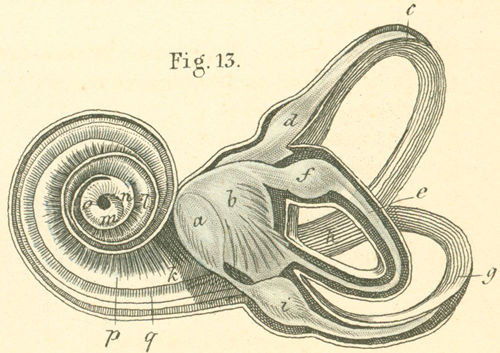

Semicircular ear canals (c, e, g). Otolith chambers (a, b). Cupula nerve regions (d, f, i). From “Handbuch der Anatomie des Menschen” published in 1841, written by Dr. Carl Ernest Bock

Positional vertigo – also referred to as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo or BPPV – has been variously treated by conventional medicine. Conventional doctors have treated all vertigo cases with chemical medications such as Meclizine, Benadryl, Diphenhydramine and others. Many of these medications have side effects such as drowsiness, blurred vision, constipation and even – believe it or not – dizziness.

Worse, many doctors have told their patients they will just have to live with positional vertigo. This ‘just get used to it’ prognosis has resulted in millions of people around the world with life-long cases of vertigo.

First, we must distinguish between vertigo and dizziness or nausea. Yes, vertigo can cause dizziness and nausea, but it is not the same thing. Vertigo is the sensation of spinning or whirling, as though the ground underneath you is turning and/or you are spinning on an upsetting carnival ride. Some describe this as whirling.

Positional vertigo also accompanies what is called nystagmus. This is a rapid fleeting of the eyes, seen while the spinning is occurring. The direction of the fleeting can indicate whether the BPPV is horizontal / lateral or vertical, as we’ll describe below.

In this article

What is positional vertigo?

Reviewing the BPPV acronym: Benign means it is not lethal. Paroxysmal means it occurs periodically with brief spells. Positional means that it is produced with changes in posture – often with changes in the head’s position, or when lying down or rising from a lying position. Vertigo refers to having a sense of motion, typically rotating or spinning, when the body is not in motion.

Positional vertigo is produced by a dislodging of the balancing crystals from the inner ear. The crystals are called otoconia, or otolyths. Otoconia are made of calcium carbonate. They are typically bound within the fluid of the otolyth labyrinth. This region includes the utricle and the saccule regions (a, b in above diagram). In these regions, normally otoconia will be reabsorbed by the cells within the otolyth chambers.

In BPPV, these otoconia crystals escape this otolyth region and leak into one of the three semicircular ducts of the inner ear (c, e, g in diagram). These round ducts also contain a fluid. When the crystals are in this fluid, they produce motion within the fluid when the head is moved. This fluid and crystal motion excites nerve endings in the inner ear. This sends sensations that the brain interprets as spinning motion.

This nerve impulse will also be sent to the eyes, which will move the eyes back and forth or up and down. This can increase the sensation of spinning.

The crystals can become dislodged into one or more of the three semicircular canals. Each of these will elicit a different set of symptoms in terms of what motions and spin motions are related to the vertigo. They also change the nystagmus fleeting of the eyes.

The most frequent scenario is called canalithiasis – where the crystals float freely in the fluid of one or multiple canals. In canalithiasis, the crystals will move after a head movement, and then settle. This will produce spinning that will stop anywhere from five seconds to a minute – with the average being about 30 seconds.

The other type of BPPV is called cupulolithiasis. This is rare, with less than five percent of BPPV patients. It produces a slower response, and can maintain a longer spinning or floating sensation in that particular position. In cupulolithiasis, the crystals are bound within the cupula nerves that are situated in the bulbs at the end of each of the semicircular canals (d, f, i in diagram).

In canalithiasis, the crystals are typically dislodged into one of the three semicircular canals – the posterior (back), the anterior (front) and the horizontal (sideways) canal.

Determining which canal the crystals is dislodged into is indicated by the direction of the nystagmus. See next section.

How is BPPV diagnosed?

Positional vertigo is best diagnosed with what is called the Dix-Hallpike maneuver:

1) Here the patient lays the head slightly back with a pillow under the back or onto a lowered section of the bed.

2) The head is leaned back about 20 degrees from the plane of the body. And the head is turned about 45 degrees to one side then the other.

3) On the side the head is turned to: If this produces the spinning sensation, this is ear with the dislodged crystals.

4) This should also be accompanied by a fleeting of the eyes. If not, then the BPPV diagnosis is questionable.

5) If that side does not provoke the vertigo, then the head is carefully turned to the other side. This should result in the spinning sensation if the first side does not provoke it.

Here is a video of the Dix-Hallpike Maneuver:

The Roll maneuver is a variation, with the patient rolling over to the other sides if the two sides do not provoke the vertigo response.

The spinning, accompanied by the nystagmus will make the eyes fleet one of three ways:

• Tortional or rotational: When the fleeting of the eyes moves in a rotational or circular path, this indicates the crystals are lodged in the posterior canal in that ear.

• Horizontal or lateral: When the fleeting is side to side in the eyes, this indicates the crystals are lodged in the lateral semicircular canal of that inner ear.

• Vertical: When the fleeting of the eyes is up and down, this indicates the crystals are lodged in the superior or vertical canal in that ear.

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver and the Roll maneuver was studied recently with 207 patients at a hospital. The doctors diagnosed 139 patients correctly on the first maneuver, and another 28 on subsequent maneuvers. Another 40 were sent to imaging testing for diagnosis.

A newer technique for diagnosis is called the vibration test. Here a mastoid vibrator (circular massage unit) is placed to the lower sternocleidomastoid muscle with a low frequency. This can provoke the nystagmus for the diagnostician.

Some doctors will also employ Frenzel goggles to film the eyes response. This allows them to record the nystagmus response for the record. These diagnostic tools do not necessarily replace the effective diagnosis using the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and Roll maneuvers.

What causes BPPV?

The risk factors for positional vertigo can be related to circulation issues, trauma or lifestyle factors.

Circulation: Migraine incidence occurs in twice as many patients as not. Vasospasms in the region or high blood pressure have been linked with BPPV. Other issues related to BPPV include diabetes or high cholesterol.

There is also some indication that smoking and heavy alcohol consumption can increase the risk of BPPV.

Sometimes BPPV may be related to a viral infection that moved into the inner ears. This may also cause vestibular neuritis. BPPV has also been associated with tinnitus and Meniere’s disease.

Head trauma – blows to the head – has also been associated with vertigo. This would also include sports where there are repeated pressures, shaking or rattling. These can include head butts in soccer or being hit by oncoming waves in surfing, for example.

Exercise that includes vibrational effects, such as mountain biking or motocross or repeated vibration training such as trampolines or vibrating plates.

In addition, long durations of sleep – especially after recovery from surgery – can provoke the dislodging of the crystals. More specifically, Ear-Nose-Throat (ENT) surgery has been associated with BPPV in some cases.

Also, sleeping on one side longer than typical has been associated with BPPV.

Another lesser known cause is dental work. A study of 768 patients with BPPV along with more than double healthy control subjects found that dental work increases the risk of BPPV by 77 percent.

The study also found that periodontics increased the risk of BPPV by more than three times (3.35) and oral surgery increased BPPV risk by more than double (2.24).

To put this in better perspective, this study also found that high blood pressure increased the risk of BPPV by 63 percent, and high cholesterol increased the risk by 46 percent. Furthermore, having migraines increased the risk of BPPV by more than four times (4.23).

Researchers from the Helsinki University Hospital studied 59 BPPV patients and found the following statistics:

• The average age at incidence was 44 years old

• 32 percent of the patients also had tinnitus

• 36 percent of the patients also suffered from headaches, and those with headaches tended to have more severe vertigo attacks

• Nystagmus was rotational in 80 percent of patients, and 47 percent also experienced floating sensations.

• Pressure change provoked most vertigo, with changes in visual surroundings also provoking vertigo.

• 52 percent had multiple vertigo attacks in a day and 26 percent had multiple attacks in a week.

Safe maneuver treatments for BPPV

As mentioned above, many doctors will still only prescribe medications to help with the symptoms of positional vertigo. These can result in numerous side effects, including dizziness and nausea. Furthermore, other doctors will tell patients they will just have to live with their vertigo.

As a result of these “treatments,” there are millions of people today who have been unnecessarily suffering from positional vertigo for years.

These have been developed by different doctors and specialists – mostly between 1986 and 2006 – who understood the mechanisms at play with the crystals in the semicircular canals. These ingenious doctors deserve great credit for experimenting with their vertigo patients and developing these safe treatment methods.

As a result of their efforts, we now have several types of maneuvers, depending upon where the otoconia crystals are trapped.

How the crystals can be moved. Courtesy University of Colorado

How effective are these BPPV maneuvers?

Medical doctors studied 113 patients who came to clinics for vertigo treatment. Of the whole group, 55 had BPPV in the right ear and 58 cases were in the left ear.

The patients were divided into three age groups: Those under 45 years old; those between 45 and 60 years old; and those over 60 years old.

Each of the patients were treated with an appropriate maneuver to return the dislodged crystals back to the otolyth chambers. The researchers saw immediate improvement in 92.5 percent of the first group, 93.6 percent of the second group and 92.3 percent of the third age group.

That is an amazing success rate. In terms of recurrence, only 5 percent of the first group had a recurrence, and 6.4 percent of the second group. The third group had a 15.4 percent recurrence rate.

Studies over ten years previous have reported higher recurrence rates after maneuvers. These have recorded recurrences nearing half the patients over three years of treatments. In most of these instances, repeat maneuvers resolved the recurrences.

In more recent studies, as we’ll discuss below, most patients’ BPPV is resolved by the newest maneuvers after home self-treatment.

Do the maneuvers have any residual effects?

We find in the above study and others that the recovery rates are phenomenally high. However, there can be residual dizziness after successful treatment.

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Neurology treated 49 patients with BPPV maneuvers. Of the group 19 had posterior canal otoconia, 1 had anterior canal otoconia, and 28 had horizontal canal otoconia.

The researchers successfully treated the patients with the maneuvers designed for each type of BPPV. This means they no longer experienced the vertigo – the spinning or whirling sensations.

Then the researchers followed up with each patient for another three months after the treatment. They found that 61 percent (30 patients) experienced residual dizziness and lightheadedness. And 18 patients had continuous lightheadedness, while 8 had periodic unsteadiness.

The average residual dizziness lasted for 16 days.

However, this residual dizziness and lightheadedness resolved itself within 20 days in practically all the patients. And within three months, none of the patients had any dizziness – and their vertigo had resolved.

The BPPV maneuvers

There are several maneuvers listed in the literature. They are intended to return the otoconia crystals stuck in the semicircular chambers back into the otolyth chambers. With each turn of the head and body listed below, the dislodged crystals will move. The point is to move them in the right direction so they return to the otolyth chamber.

The maneuvers must be done precisely and with the right timing listed. This allows the crystals to move in the right direction, and with enough momentum to reach their intended destination.

Here we will summarize and give you a video to watch for each type of maneuver. Note that most of these can be done safely at home, but it is advised that a health professional expert in these maneuvers provide the diagnosis and teach the maneuver the first time. Then the patient can do the maneuver at home if the initial treatment doesn’t fully resolve the symptoms.

The reason is that doing the wrong maneuver – or doing the maneuver wrong – can result in moving the otoconia into other parts of the canals. This can require additional treatments.

Here is a review of maneuvers:

Posterior canal otoconia

Remember this is characterized by tortional or rotational fleeting movements of the eyes.

The standard treatment for posterior canal otolyths has been the Epley Maneuver:

1) The patient lays on a table with head tilted back by 20-30 degrees from the plane of the back.

2) The head is then brought to the side (patient still lying on back) of the ear with affected ear. This position (head to the side and 20-30 degrees from the plane of the back) is held for 30-60 seconds. The eye fleeting should occur here.

3) After the fleeting (spinning sensation) stops – the head is then rotated to the other side for 30-60 seconds, keeping that same back angle of 20-30 degrees.

4) Then the patient rolls to their shoulders on that side, and turning the head to about 45 degrees from the horizontal on that side, for another 30-60 seconds.

5) From that shoulder-side movement, the patient sits directly up.

Here is a video of the maneuver:

Another maneuver for the posterior canal BPPV is called the Half Somersault Maneuver or the Foster Maneuver – developed by Dr. Carol Foster.

This maneuver is newer, but it also has been shown to be more effective. A study from the University of Colorado tested 200 patients per year between 2007 and 2010. They found that while both treatments were successful, there were more failures with the Epley Maneuver.

After home treatments, 90 percent of the patients had a complete resolution of both vertigo and dizziness in the Half Somersault group. In the Epley group, 67 percent of the patients had a complete resolution.

This study also found that there was less residual dizziness in the Half Somersault group. This study also commented:

“Usually patients with recurrences return to clinic for further maneuvers, but home exercises should be more cost-effective.”

Here is a summary of the Half Somersault:

1) Sit on knees with hands on the floor and neck arching back 45 degrees. Hold for 15 seconds following no dizziness/vertigo.

2) Move head down into a somersault position, tucking chin in as far as possible and keeping hands on the ground. Hold for 15 seconds.

3) Turn head to face the elbow of the affected ear, about 45 degrees. Hold for 15 seconds after any dizziness.

4) Keeping head turned to the side at 45 degrees, lift head up by pushing up from the hands (knees are still on the ground). Hold for 15 seconds.

5) Now raise head upright to the plane of the back, keeping head at 45 degrees. Hold for 15 seconds.

6) Then one can sit up, relax and get up. One should wait at least 15 minutes before repeating the maneuver.

Here is a diagram of the Half Somersault maneuver:

Courtesy University of Colorado

Here is a video of the Half Somersault maneuver:

Horizontal or Lateral canal otoconia

Remember that this is symptomized by fleeting from side to side in the eyes when doing the Dix-Hallpike diagnostic test.

The Lampert Maneuver has shown great efficacy for this type of BPPV:

1) Lay on back and turn head 90 degrees to the side with affected ear for 30-60 seconds.

2) Turn down onto elbows with face towards table or bed and back up for 30-60 seconds.

3) Now turn to the next side onto shoulder with head rotated another 90 degrees to the next side. Lay head onto hands. Hold for 30-60 seconds.

4) Roll over to the back-lying position – to the beginning position. Hold for 30-60 seconds.

5) Now you may slowly get up. This can be repeated no more than once a day.

Here is a video of the Lampert maneuver:

Anterior (or superior) canal otoconia

Remember, this is diagnosed with the fleeting of the eyes being vertical – up and down. The maneuver used is called the Deep Head Hanging Maneuver:

1) Lie back on table or bed with head hanging completely back over the side. This should cause the eye fleeting and spinning. Hold for 30-60 seconds after vertigo is completed.

2) Continuing to lie, bend head forward with the chin coming to the chest. Hold for 30-60 seconds.

3) Now sit up straight.

Here is a video of the Deep Head Hanging maneuver:

REFERENCES:

Evren C, Demirbilek N, Elbistanlı MS, Köktürk F, Çelik M. Diagnostic value of repeated Dix-Hallpike and roll maneuvers in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016 Apr 22. pii: S1808-8694(16)30039-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.03.007.

Chang TP, Lin YW, Sung PY, Chuang HY, Chung HY, Liao WL. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo after Dental Procedures: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. PLoS One. 2016 Apr 4;11(4):e0153092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153092. eCollection 2016.

Chiarella G, Leopardi G, De Fazio L, Chiarella R, Cassandro E. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo after dental surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Jan;265(1):119-22.

Gyo K. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a complication of postoperative bedrest. Laryngoscope. 1988;98(3):332–3.

Zhang H, Li J, Guo P, Tian S, Li K. Efficacy of quick repositioning maneuver for posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in different age groups. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015 Dec;29(23):2053-6.

Vibert D, Redfield RC, Hausler R. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in mountain bikers. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116(12):887–90.

Kentala E, Pyykkö I. Vertigo in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000;543:20-2.

Imai T, Takeda N, Ikezono T, Shigeno K, Asai M, Watanabe Y, Suzuki M; Suzuki on behalf of Committee for Standards in Diagnosis of Japan Society for Equilibrium Research. Classification, diagnostic criteria and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016 May 9. pii: S0385-8146(16)30107-9. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2016.03.013.

Seok JI, Lee HM, Yoo JH, Lee DK. Residual Dizziness after Successful Repositioning Treatment in Patients with Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Journal of Clinical Neurology (Seoul, Korea). 2008;4(3):107-110. doi:10.3988/jcn.2008.4.3.107.

Foster CA, Ponnapan A, Zaccaro K, Strong D. A Comparison of Two Home A Comparison of Two Home Exercises for Benign Positional Vertigo: Half Somersault versus Epley Maneuver. Audiol Neurotol Extra 2012;2:16–23. DOI: 10.1159/000337947.

Fife TD. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Semin Neurol. 2009;29(5):500-508.