Antibiotic Overuse in Childhood Causes More Illness Later

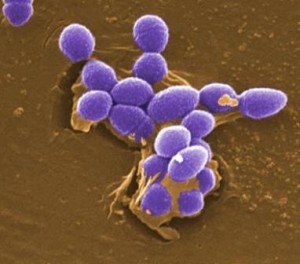

Image by Pete Wardell

Gradually we are finding that modern medicine’s unabated use of antibiotics for minor and often viral infections has many unintended effects.

The most obvious – as we have discussed many times in this publication – is the increase in antibiotic-resistance among bacteria. This is increasingly causing infections that no longer can be treated with antibiotics.

Now to add to this issue, the overuse of antibiotics among children has been found to cause yet another unintended consequence: A lower immunity in the child’s later life.

In other words, the more antibiotics a child is given during children, the more illnesses and infections the child will face later in life.

In this article

Children are given lots of antibiotics

About a quarter of all medications prescribed to children in the U.S. are antibiotics. And about a third of these antibiotics have been described by multiple papers as unnecessary.

Antibiotics are systematically prescribed to children for ear infections, colds, coughs and sore throats. Many of these infections will resolve themselves. And sometimes antibiotics are given when the source of the infection is a virus – such is the case of many coughs, sore throats, colds and even some ear infections. For viral infections, an antibiotic will have little or no effect other than to cause a die-off of fledgling but important probiotic bacteria within the child’s gut and oral cavity.

Early gut health is sensitive

Research has found that the first three years are critical for the development of the child’s gut microbiome. This means that antibiotics given during this period may seriously interrupt the natural development of microbes.

The issue is diversity. The sheer number of species. The more species of probiotic bacteria the gut has, the healthier the person will be. Studies have shown that the number of species after the age of three will be double or more of the number of species in a child under three years of age.

Childhood antibiotic use decreases gut health

A number of recent studies have shown that children given repeated doses of antibiotics will have an increased incidence of digestive issues later in life.

Multiple epidemiological studies published between 2005 and 2012 were vetted and analyzed by researchers from the University of Minnesota. Led by Dr. Dan Knights, a biologist and professor in the University of Minnesota, the data from the different studies was compiled and meta-calculated.

Dr. Knights reflected on the research:

“Previous studies showed links between antibiotic use and unbalanced gut bacteria, and others showed links between unbalanced gut bacteria and adult disease. Over the past year we synthesized hundreds of studies and found evidence of strong correlations between antibiotic use, changes in gut bacteria, and disease in adulthood.”

The research found that the more antibiotics a child is given during child, the worse off their gut microbiome will be. This leads to an increased incidence of what is called gut dysbiosis.

Adult diseases linked to child antibiotic use

The computational research found that antibiotic use in children led particularly to increased risk of allergies, obesity, developmental issues, autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases.

The mechanisms relate to the health of the intestinal wall and the maturity of immune cells. For example, Dr. Knights and his research associates developed a model that showed how destroying important probiotics in childhood prevented immune cells to mature, and this led to greater risk of allergies and reduced immunity.

The diagram below illustrates how antibiotics disrupt the development of the gut’s bacteria:

Image courtesy of Dan Knights and Cell Host & Microbe

Progressive gut bacteria maturity measured

The computational analysis by the researchers also led to the ability to map out how the child’s age and gut health can be measured. This allowed them to develop a “gut age” determined by the relative health of the colonies of probiotics within the intestines of the child. A child with fewer healthy colonies would be considered less “mature” in terms of their gut health.

This mapping could allow doctors in the future to look at a child’s gut health and determine whether the child’s gut health is maturing in a healthy manner.

Note: This article is not intended to discourage parents from following their doctor’s prescribed treatments for their children. Whatever decision is made regarding a child’s treatment should be discussed with a pediatrician.

Probiotics Simplified: How Nature’s Tiny Warriors Keep Us Healthy

REFERENCES:

Vangay P, Ward T, Gerber JS, Knights D. Antibiotics, Pediatric Dysbiosis, and Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2015 May 13;17(5):553-564. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.006.

University of Minnesota Press Release. Infant antibiotic use linked to adult diseases. May 13, 2015.

Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Amenyogbe N, Brown EM, Finlay B. The intestinal microbiome in early life: health and disease. Front Immunol. 2014 Sep 5;5:427. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00427.

Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012 May 9;486(7402):222-7. doi: 10.1038/nature11053.

Matamoros S, Gras-Leguen C, Le Vacon F, Potel G, de La Cochetiere MF. Development of intestinal microbiota in infants and its impact on health. Trends Microbiol. 2013 Apr;21(4):167-73. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.12.001.

Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, Angenent LT, Ley RE. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Mar 15;108 Suppl 1:4578-85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107.